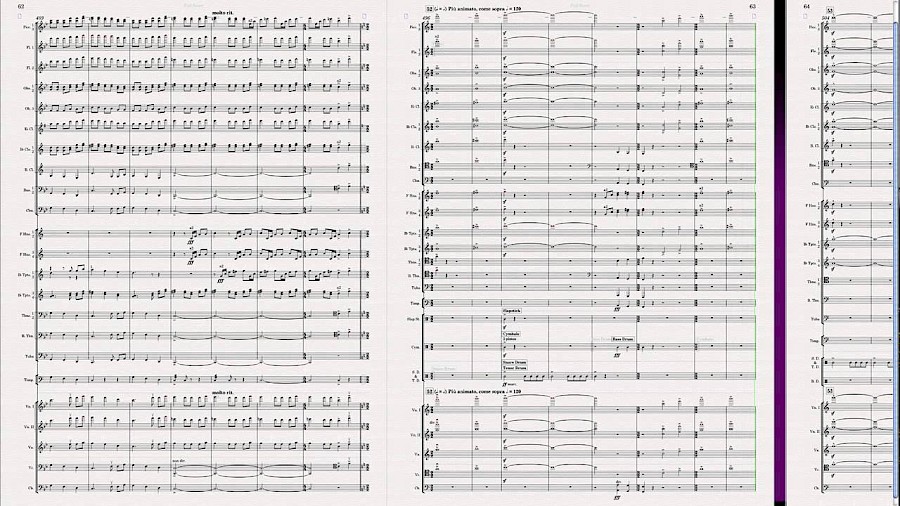

Copland wanted his music to be heard. For him (and most composers in the classical tradition), that meant writing it down so that other musicians could play it. The written score communicated his imagined musical ideas to performers, who could turn the marks on the page into sound waves that listeners could hear.

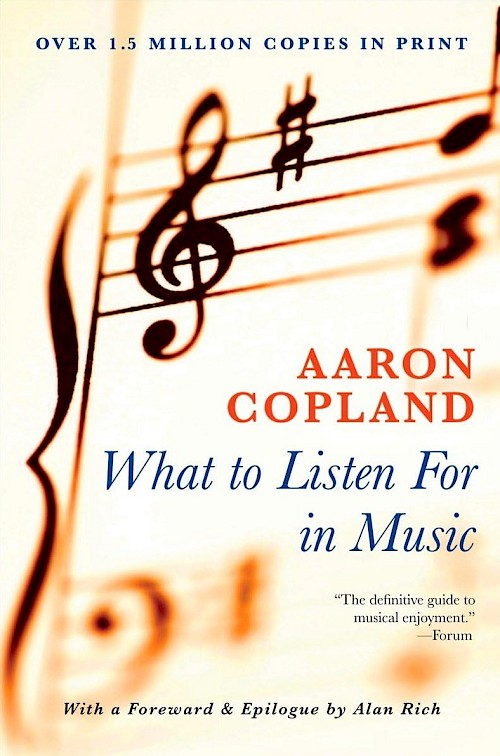

In his famous music appreciation book What to Listen for in Music (1937), Copland wrote, "...the interpreter is a kind of middleman in music. It is not so much the composer that the listener hears, as the interpreter's conception of the composer." He refers to performers as interpreters, in part to emphasize their responsibility to the score. "The writer's contact with his reader is direct; the painter's picture need only be hung well to be seen. But music, like the theater, is an art that must be reinterpreted in order to live.” (What to Listen for in Music 159-160)

Unperformed music, whether notated or existing only in the composer’s imagination, is just an idea.

Notation and editions

Especially when musical ideas are lengthy, specific, or complicated, notation can be very helpful for communicating with performers. Music notation is a system of written symbols that represent the sounds imagined by the composer. As with any communication system, the performers and composer have to agree on the meaning of the symbols.

Of course, in many cases, notation isn't really needed to get music into the ears of listeners. Some composers perform their own music; others write for electronic reproduction by computers or other machines. (Audio engineers can play the role of what Copland called the "middleman" these days.) Still other composers—famously, John Cage—leave so much up to the performer's discretion that the very notion of authorship is disrupted. And certainly improvised music—such as some types of experimental music and jazz—is less notation-dependent than the typical classical piece.

Yet, most music written for the concert hall still relies heavily on notation. Wind ensembles from The “President’s Own” U. S. Marine band to football half-time ensembles to school bands across America use notation. Much of the music heard in moving pictures, Broadway shows, church choirs, folk and traditional music gatherings, and jazz education programs was disseminated or learned with the help of notation.

That is where an edition comes in. An edition is a version of a score (and when appropriate, the parts for each individual instrument) made to be reproduced and distributed so more people can play it and hear it.

Editions 101

As one learns in music school, there are two basic types of music editions: performance editions and scholarly editions, which are sometimes called critical editions. An excellent overview can be found on the Indiana University Libraries website. Here, I'll focus on performance editions.

Performance editions are eminently practical, and from a composer’s perspective, the most crucial. Their purpose is to convey a composer's musical ideas to the performers who will then turn those ideas into physical sound waves that can reach the ears of listeners. For any composer, getting performances is the ultimate goal. Even worse than the proverbial tree falling in the forest is a composer's detailed plan for a complex musical creation that no-one ever hears.

The limits of notation

The performer, in Copland's view, must adhere to the composer's conception. "The role of the interpreter leaves no room for argument. All are agreed that he exists to serve the composer—to assimilate and recreate the composer's 'message,'" he wrote in What to Listen for in Music (159).

Yet Copland also understood the limits of notation. "Musical notation, as it exists today, is not an exact transcription of a composer's thought," he continued. "It cannot be, for it is too vague; it allows for too great a leeway in individual matters of taste and choice." Even if notation itself were precise, he acknowledged, "Composers are only human—they have been known to put notes down inexactly, to overlook important omissions. They have also been known to change their opinions in regard to their own indications of tempo or dynamics." (What to Listen for in Music 160)

This was not a passing thought. Nearly twenty years later, he wrote, "Some performers take an almost religious attitude to the printed page: every comma, every slurred staccato, every metronomic marking is taken as sacrosanct. I always hesitate, at least inwardly, before breaking down that fond illusion. I wish our notation and our indications of tempi and dynamics were that exact, but honesty compels me to admit that the written page is only an approximation; it's only an indication of how close the composer was able to come in transcribing his exact thoughts on paper." (Music and Imagination 49-50)

His ultimate antidote was better communication between interpreters and contemporary composers—a goal he stated in the 1950s and later conveyed in the founding documents for the Aaron Copland Fund for Music.

Why bother with notation at all, then?

In our post-colonial society, new respect has emerged for the idea that writing is not the only way humans have codified and transmitted knowledge. Aural tradition, embodied knowledge, and even the idea of intergenerational trauma are three such subjects of recent interest to those who study and teach the history of music. Even when considering only notated music, more variety exists than was previously recognized by the Western art music-focused circles within which Copland operated.

Nonetheless, Copland had at his disposal, and benefitted from, a remarkable notation system that developed more or less continuously in Europe for nearly a thousand years. That system is flexible enough and widely enough understood that it can passably convey (or approximate) the musical ideas of composers as different as Machaut, Wagner, and Sondheim. Most classical musicians—and many others—find Western music notation incredibly useful. Today, many of the best minds in composition, notation, and software development continue to use and adapt it to meet emerging needs.

Performance editions of Copland’s music

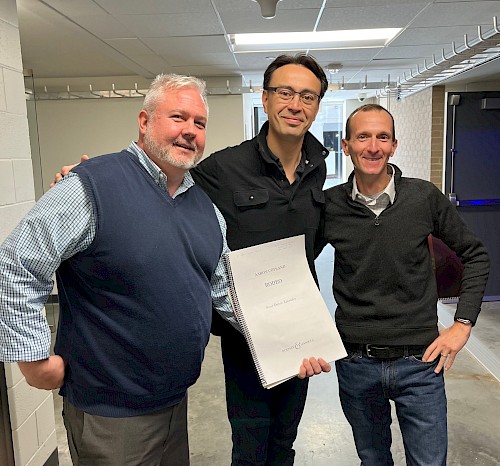

One of those minds is Philip Rothman, whom the Copland Fund engaged about fifteen years ago to make new performance editions of many Copland works. Known in the industry for his award-winning company NYC Music Services, Rothman's expertise is in music copying and computer engraving, music transcription, score transposition for vocalists, and orchestration for television and movie scores.

In a 2014 blog post on his multifaceted website, Scoring Notes, he described the project thus: "Over the past several years, I’ve had the good fortune to re-engrave several of Aaron Copland’s greatest works, in cooperation with The Aaron Copland Fund for Music and Boosey & Hawkes. One of the main purposes of these new engravings was to make a clear set of performance materials—score and parts—that improved upon what had been circulating for decades, both in the accuracy of the music and its presentation on the page." (“Road report: Copland 3 in The Big Easy”)

Especially for Copland's orchestral and chamber works, he explains, the logistics and mechanics involved in a live performance—and rehearsals—have been an important consideration. Is the layout of the score clear and legible? Is there adequate time to turn the page? Are the measure numbers consistent, and are they located in helpful places, where the performers might want to start rehearsing?

With any performance edition, if the composer's intentions aren't crystal clear, the editor steps in. Editors will fix any obvious errors made by the composer or earlier editors and will reconcile any discrepancies that may exist between different versions of the score. While some editors will add phrase markings and may even suggest which fingerings a performer should use, Rothman's policy is conservative; he will add only what seasoned performers feel is essential to convey Copland's original intentions—which are, for most Copland works, easily traceable through the well-organized sketches and manuscripts Copland donated to the Library of Congress.

One score at a time, Rothman has been tackling those Copland works that would benefit most from new editions. Titles are prioritized for re-engraving based on multiple criteria: the work's popularity—or its potential for increased performances—and the condition of the materials. A work like Rodeo was (and remains) in high demand, so it made sense to correct known errors and improve the layout. Other works may be less popular, in part, because difficult-to-read materials make performances difficult. Three Latin American Sketches, the original performance materials for which were problematic, was re-engraved in hopes of encouraging and facilitating more performances of this audience-pleasing work. ("Three quick tips from engraving Copland")

To date, he has overseen the creation of editions of Appalachian Spring (four distinct versions), Billy the Kid Ballet, Billy the Kid Suite, Clarinet Concerto, Old American Songs (Sets 1 and 2), Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo, Rodeo Complete Ballet, Third Symphony, and Three Latin American Sketches. Next in line is an edition of the Piano Concerto. His blog reports about the Third Symphony ("Road Report: Copland 3 in The Big Easy"), Appalachian Spring ("Creating new versions of Appalachian Spring using Sibelius and Norfolk"), Rodeo ("Road report: Copland’s Rodeo in Milwaukee") and Billy the Kid ("New edition of Copland’s Billy the Kid ballet with Peabody Orchestra") editing projects are filled with engaging stories of encounters with famous personalities, as well as examples of the way individual conductors, performers, and librarians play a crucial role in the process of edition-making.

Beyond a Mere Blueprint

The goal of a performance edition is to create the clearest, most accurate, most efficient path from composer's conception to performer's realization. When there is a discrepancy, an omission, or an error in the notated score, the editor of a performance edition will solve the problem and incorporate that solution into the score, suggesting the right outcome to the performer.

Scholarly editions approach discrepancies somewhat differently. While the editor may present the same solution in the printed score, he or she will make a point of acknowledging all possible solutions for each discrepancy, presenting the available evidence for each. The purpose is to allow the performer or scholar to decide for themselves. Needless to say, the quantity of information presented can quickly make a published volume too unwieldy for use in a live performance.

For instance, when Rothman created high-voice and low-voice editions of the Old American Songs (voice-and-orchestra scoring), he made some minor changes to Copland's original pitches and orchestration to accommodate the range limitations of various instruments. Since these are performance editions, each individual change is not marked in the score, nor was it necessary to append a chart listing every change. Instead, a prefatory note reads "This adaptation ... differs from the original keys but otherwise is as similar as possible to the original orchestration, adjusting only to account for instrument ranges."

Two of Rothman's recent performance editions, the Clarinet Concerto and the Third Symphony, incorporate elements of a scholarly edition. As described in the Editors’ Notes to the score (pages v and vi), the Clarinet Concerto edition includes both the original and revised versions of a passage that Copland rewrote at the request of Benny Goodman, who commissioned the work. The new Third Symphony edition includes both Copland’s original ending and the shorter, alternate ending popularized by Leonard Bernstein, which appeared in the 1966 edition. Such significant decisions about well-known works are never made lightly. In keeping with scholarly practice, the prefaces to both editions describe the sources consulted, provide historical context, and acknowledge the collaborators whose research and expertise lay behind these new engravings.

Readers fond of scholarly mysteries and editorial intrigue are invited to return for the second part of this series to explore a new horizon: critical and scholarly editions of Copland’s music.