The years 1941 and 1942 were exceptionally eventful for Copland and his country. The U.S. entered World War II while the 41-year-old composer was entering the height of his career. In two short years he finished five of his most enduring works: Rodeo, Fanfare for the Common Man, Lincoln Portrait, Danzón Cubano, and the Piano Sonata. Such productivity did not occur in isolation. These "Early War Years," as he called them, were interwoven with musicians, patrons, and other colleagues. His professional growth amidst the upheavals of World War II is best understood through the networks of people who, like Copland, wanted to perform, promote, study, hear, write about, and compose new music.

As Copland recounts these years in his autobiography, four somewhat distinct (though overlapping) professional networks emerge. I've given each a location-based name, but don't think of them as points with fixed geographical borders. Rather, each network of relationships was formed or reinforced through a place. Of course, he was building networks in other places, too, most notably Hollywood and Europe, but from 1940 into 1942, these four dominated. For the purposes of this article, I am less concerned with sorting people "correctly" than I am with introducing them in a meaningful context; and once someone entered Copland's networks, they usually crossed paths again elsewhere.

Network 1: New York City

In 1941, as today, New York City was known as the cultural capital of the United States; a crucible for artistic creativity at the highest level: theater, dance, classical music, opera, musical theater, writing and the visual arts. The performing arts thrived through face-to-face interaction, and Copland was at the center of it all. His professional networks in New York started early and lasted a lifetime.

The League of Composers

Copland's most enduring circle formed through the League of Composers, a group begun in 1923, the year before he returned from France. The League's purpose was to give contemporary composers performance, funding, and publishing opportunities, and provide exposure to the latest trends in concert music. One of the League's founding composers was Marion Bauer (b. 1882), an earlier pupil of Boulanger; she met Copland in Paris in 1923 and recommended the League to him.

Three organizers of the League of Composers were lasting presences in Copland's career: Claire Reis (b.1888), Minna Lederman (b.1896) and Alma Morgenthau Wertheim (b.1887). Lederman was founding editor of the League's journal, Modern Music (1924-1946), which became the principal forum for discussion of contemporary composition in the U.S. Reis, raised in Texas, studied piano in Europe and at the precursor to the Juilliard school. Daughter of American businessman and diplomat Henry Morgenthau, Sr., Alma Wertheim and her investment-banker husband were art collectors—including of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work; after their divorce she provided a monthly subsidy for Modern Music, among other philanthropic activities.

Copland took leadership in the League early. He worked closely with Wertheim to establish Cos Cob Press (1928, which became Arrow Music Press in 1938). With composer Roger Sessions, he started a concert series, the Copland-Sessions concerts (1928-1931), and he organized and participated in countless other League-related music series around the city. With Bauer, Virgil Thomson, and others, he founded the American Composers Alliance (1937-present), which according to its website, aims “to make [American] music available to orchestras and performers, and to be sure that composers were compensated fairly and credited for performances of their work.” With Bauer, Howard Hanson, Henry Moe and others, in 1939 he started the American Music Center, a score lending library and music service organization (which, in 2011, was folded into New Music USA; some of the scores are now archived at the New York Public Library). Moe was also the administrator of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, which awarded its first fellowship in music composition to Copland in 1925. By the early 1940s, Copland had established a strong relationship with the Foundation, recommending many other winning composers through the 1930s and following decades.

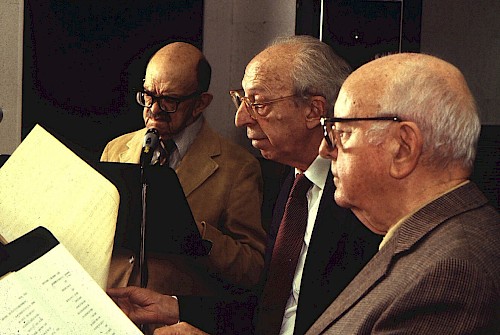

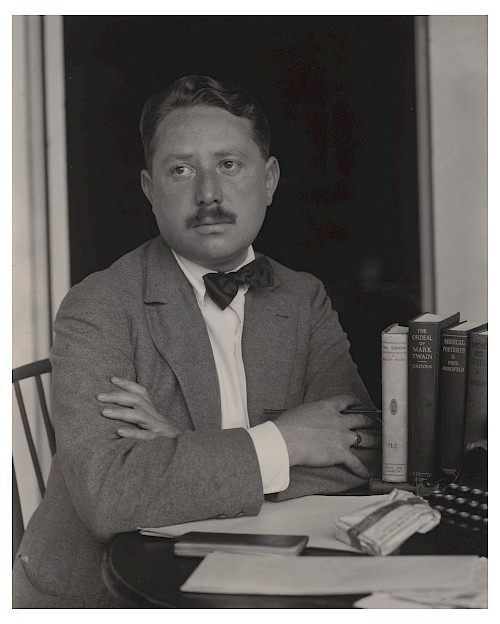

Paul Rosenfeld

A crucial supporter of Copland and the League was Paul Rosenfeld (b.1890). Rosenfeld was not a musician, but he "believed passionately in the emergence of an important school of contemporary American composers," Copland later recalled. "[He] invited me to dinners at his apartment on Irving Place with the most interesting people in the avant-garde literary, music, and art worlds: [...] Hart Crane, Lewis Mumford, Waldo Frank, e.e. cummings, and Edmund Wilson." Rosenfeld connected Copland with a network of patrons who provided financial support, housing, and/or workspace for composers. This network included not only Wertheim and Lederman but Marian MacDowell (founder of MacDowell) and the Trask family (who founded Yaddo), both a short drive from New York; and in the 1930s Mary and William Lescaze and Peggy Bernier.

Rosenfeld was also an early link to the longstanding New York City network of authors, critics and writers about modern composition. Copland recalls, "Paul was one of the first critics to write perceptively about Ives, Ornstein, Varèse, Ruggles, Cowell, Harris, and Sessions." (Complete Copland 43).

Other peers and collaborators

An essential member of Copland's New York network was stage director Harold Clurman (b. 1901) and his Group Theatre, which included playwright Clifford Odets (b.1906), who in the late 1930s commissioned Copland's Piano Sonata. Clurman was a distant cousin of Copland’s; the two were roommates in Paris, where Clurman studied at the Sorbonne. Fifty years later, Copland considered Clurman one of the three “major and continuing influences” in his life (Complete Copland 23), especially for ideas in the other arts and politics (Complete Copland 233).

Other writers in his New York circle included composer-critics Virgil Thomson and Arthur Berger. Thomson was an important League-connected peer, who lived mostly in Europe from 1925-1940, and he wrote for Modern Music as a correspondent before he moved back to New York in 1940 and began a legendary career as the music critic for the New York Herald Tribune. Berger was a native New Yorker who wrote the first book about Copland (1953) just before moving to Boston where he became an influential professor and administrator.

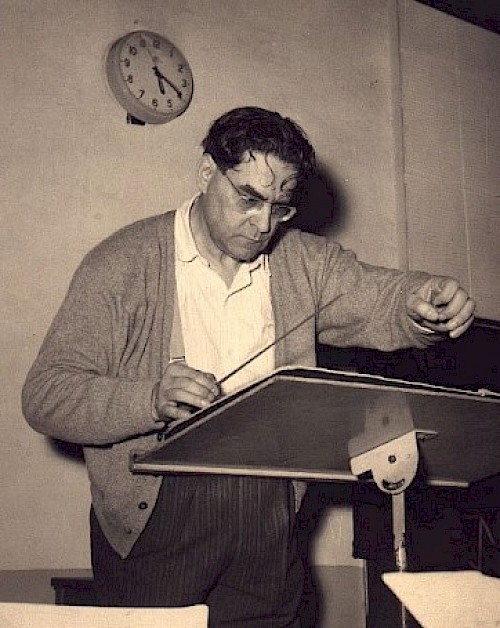

Network 2: Boston and Tanglewood

Copland's Boston/Tanglewood network had deep roots in his long relationship with conductor Serge Koussevitzky. The two men first met in 1924 through Nadia Boulanger, Copland's teacher near Paris, when Koussevitzky was passing through en route to his first season as Boston Symphony Orchestra director.

Serge Koussevitzky

Koussevitzky's appointment in Boston represented a deliberate departure from the deeply Germanic tradition that had dominated many American orchestras, partly as a reaction to World War I, during which major US orchestras switched from conducting rehearsals in German to English.

From the time they first met, Koussevitzky championed the young Copland, conducting premieres of major works including the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra and the Piano Concerto, bringing the composer to national prominence despite controversy in conservative Boston circles. Their relationship deepened over the years as Koussevitzky pursued his personal dream of establishing a summer music institute, something he had been lobbying for and building toward for many years.

When Koussevitzky finally realized his vision and the Tanglewood Music Center was opened in 1940, Copland's participation was a foregone conclusion. Copland established himself as a central figure in what would become one of America's most influential musical networks, mentoring students who would define American music for decades to come.

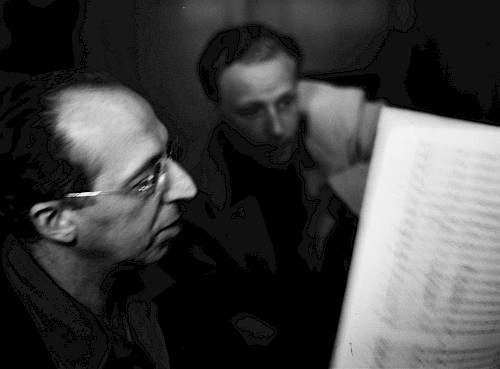

Leonard Bernstein

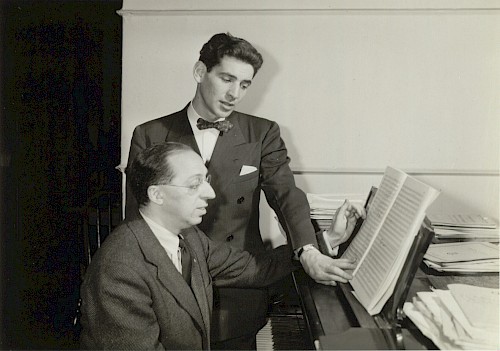

The not-yet-famous Leonard Bernstein was merely an exceptionally promising student at Tanglewood in that first summer. He later became a fixture there, but in 1940, he was a newly minted Harvard grad who during a junior-year excursion to New York, had met Copland through happenstance and impressed the composer by performing the Piano Variations for him.

Recalling the early war years, Bernstein said, "I worried and complained terrifically during the early forties and always took my troubles to Aaron, who would tell me to 'stop whining.'" (Complete Copland 141-143). Bernstein, Copland, and Koussevitzky were quite the trio at Tanglewood in 1940 and 1941, with the elder conductor becoming like a father figure to the young Bernstein. This mentorship proved prescient when Bernstein suddenly rose to fame in 1943 as a last-minute substitute conductor for an ailing Bruno Walter at a nationally broadcast New York Philharmonic concert at Carnegie Hall—coincidentally on Copland's birthday—launching his international career. Their friendship, documented in voluminous correspondence, spanned nearly five decades, from 1941 until their deaths, months apart, in 1990 and resulted in professional collaborations too numerous to recount here.

Tanglewood Faculty and other Boston-area musicians

Copland's Tanglewood/Boston network had an international dimension, as European composers including Paul Hindemith and Bohuslav Martinů, who joined him as faculty at Koussevitzky's invitation. World War II limited the international exchange of music. The war also significantly impacted Tanglewood's operations, with the Boston Symphony not performing there in 1942, and from 1943 to 1945, neither the Boston Symphony nor the Tanglewood Music Center operated.

Though less directly connected with Tanglewood, other Boston-area musicians were important people in Copland's professional life. Nicolas Slonimsky (b.1894), Koussevitzky's secretary and pianist in the 1920s, was an early Copland contact in the Boston area. The future author of The Lexicon of Musical Invective impishly sent Copland a pack of scathing local reviews after Koussevitzky premiered Copland's Piano Concerto, and in 1941, he crossed paths with Copland in Latin America.

A number of composers in the Boston area, sometimes called "New England School" or "The Harvard Neoclassicists," included many composers who were sympathetic to Stravinsky and Copland. Irving Fine, Harold Shapero, Arthur Berger, Lukas Foss, Bernstein, and Walter Piston are often included. Irving and Verna Fine became good friends who sometimes hosted Copland during his summers in Tanglewood.

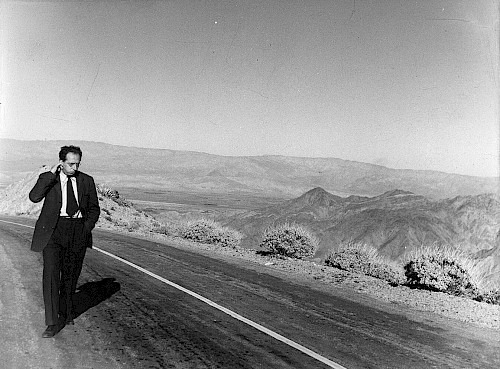

Network 3: Latin America

When Tanglewood's second summer season ended, Copland embarked upon his first government-sponsored diplomatic tour. He spent 3 1/2 months (August 20 - December 9, 1941) traveling in Mexico, numerous South American countries, and Cuba. He gave lectures in Spanish, met with university and government administrators, interacted with composers and music students, and attended concerts of their music and of music by Copland and his peers. He returned via Cuba only days after Pearl Harbor was bombed and the U.S. entered World War II.

"Such an experience enlarges one’s field of vision," Copland reflected in his diary upon his return. "It made me feel concern for the provincialism that seemed to be typical of the music scene in New York, where there was a small circle of composers encouraging each other."

Copland’s Tour Connections

Copland had been friends with Mexican composer-conductor Carlos Chávez (b. 1899) since the 1920s. By the time Copland returned from his studies in Paris, Chávez had worked in Europe and New York. From an influential Mexican family, Chávez bonded with Copland over their shared desire to create a modern national style that would speak to broad audiences in their respective countries. Four students of Chávez, the “Grupo de los Cuatro” after the Russian “Mighty Five” and “Les Six” of France, were busy creating a new Mexican national school of composition. Copland had already met Blas Galindo at Tanglewood in the summer of 1941; he connected with the other three—Daniel Ayala, Salvador Contreras, and José Pablo Moncayo—on the first leg of his 1941 tour.

Over the next three months, Copland would meet countless composers from different countries, some of whom would remain friends and contacts throughout the rest of his career. In Argentina, he met Alberto Ginastera, who, though only 25 was "far ahead of any of the young men of his age here," and the "most likely to profit by contacts outside Argentina." (Complete Copland 137). In Brazil, Copland met Heitor Villa-Lobos, already known in the U.S. as the country's most prominent composer, and the two drove into the countryside to experience folk music. He met Domingo Santa Cruz, the "foremost musical figure" in Chile (Complete Copland 137), who had enlisted the help of composers and artists and was running an outstanding Faculty for Fine Arts.

In Uruguay, Copland met Juan José Castro (b. 1895), who led a performance of An Outdoor Overture with Argentina’s Colón Orchestra. The European-trained Argentinian composer-conductor, a professor in Buenos Aires and an active conductor in neighboring countries, made a strong impression. By the end of that year, the League of Composers had organized a concert devoted to Castro’s music at the Museum of Modern Art in New York at Copland’s suggestion.

Integrating Networks

Back in the U.S., Copland began integrating these new connections to his existing networks. He extracted an article on “The Composers of South America” from his 78-page diary; Minna Lederman promptly published it in the next issue of Modern Music. The Juan José Castro concert occurred a few weeks later in New York, and Copland introduced Castro for consideration by the Guggenheim awards committee. Many Latin American composers in subsequent years received fellowships to Tanglewood.

In his autobiography, Copland reflected, "I am told that my 1941 expedition opened the way for many Latin American musicians to make contact with the world of concert music. For me, it was the beginning of friendships and associations that would continue through many years." (Complete Copland 139). The months abroad gave him a new perspective about his active but familiar New York City network. The New York circles had been going strong for more than fifteen years, but Latin America was a new starting point; it helped propel him beyond his "provincial" city.

Network 4: Washington, D.C.

Before his Latin American tour, Copland was not unknown outside New York; Koussevitzky programmed him often in Boston; Boulanger championed him from her influential teaching post in France; his first Hollywood scores, Of Mice And Men (Dec 1939) and Our Town (May 1940), were introducing his music to American movie-goers; his first verifiable hit, the ballet score to Billy The Kid (1938), and its folktune-travelogue cousin El Salón México (1937) were finding favor with orchestras nationwide. Nonetheless, it was Washington, D.C. that played a crucial role in Copland's transformation from "best-known American modernist composer" to national figure, endorsed by the federal government, and worthy of representing of his country's culture on the international stage. Of all the professional circles operating in Copland's career, this network uniquely exceeded geographical boundaries.

Tour Affiliates

The Library of Congress and State Department affiliates who planned and funded his 1941 tour were well connected: experts in diplomacy, familiar with Latin America, and interested in contemporary American music. Three important D.C. connections for that tour were Carleton Sprague Smith, Gilbert Chase, and Charles Seeger.

Carleton Sprague Smith coordinated musical activities for Nelson Rockefeller’s Committee of Inter-American Affairs. (Complete Copland 136) Rockefeller, then just 25, headed that committee as an Assistant Secretary of State for the U.S. State Department. Sprague Smith was the music specialist, and Copland sent his post-tour report to him.

Gilbert Chase, a Cuban-born American writer/scholar specializing in music of the Americas, was the Latin American Music Specialist at the Library of Congress from 1940-43. While employed by the Library of Congress, he advised Copland's first diplomatic tour of Latin America and would later write about Copland in his celebrated 1955 book America's Music: From the Pilgrims to the Present. Through Chase’s involvement in planning the tour, Copland also met Harold Spivacke, chief of the Library of Congress’s Music Division.

Charles Seeger helped plan the trip as chief of the Music Division of the Pan American Union, an inter-governmental association and predecessor to today's Organization of American States. An American born in Mexico, Seeger had broad interests in composition, folklore, and political philosophy. He and Copland had been previously introduced by Henry Cowell in New York, but since 1936, Seeger had lived in Washington, D.C. with his family, holding various music-related posts during the Roosevelt presidency. He was married to modernist composer Ruth Crawford (and father of Pete, Mike, and Peggy Seeger).

Networks & Patriotism

When the U.S. became a country at war, composers in Copland's networks wanted to make a difference. In Copland's case, though Lincoln Portrait and Fanfare for the Common Man were not official government commissions, they arose directly from Copland's proactive efforts to be involved as a composer in the war effort, a conviction also shared by composer William Schuman. Both composers corresponded with Harold Spivacke at the Library of Congress, requesting to serve, and Schuman, still in his 30s, tried to become an officer in the Army.

In 1942, Copland's D.C. contacts arranged high-profile performances of the newly completed Lincoln Portrait and Fanfare for the Common Man at symbolic national gatherings. About the same time, the Library of Congress initiated its commission of what would become the great Aaron Copland-Martha Graham collaboration, Appalachian Spring, brokered by Spivacke. Promoted by government music advisory committees, Copland's music became standard for military bands, U.S. embassies, and inaugural committees.

Local, national, and international concerns intersected for Copland in Washington. By 1963, the government had sent him abroad 11 times, including trips to Russia, Japan, Australia, Europe, and South America. In this way, D.C.-based institutions and people played a crucial role in transforming Copland and his music into symbols of the U.S.

Conclusion

In these "Early War Years” Copland’s home network, in New York City, expanded tremendously. Building on the strong relationship with Koussevitzky, his Boston network expanded to include Tanglewood and its ever-growing cast of colleagues and students from across the country and beyond. His extended tour of Latin America not only solidified his connections in Washington D.C., but broadened his perspective in a life-changing way. These four networks built upon earlier-established connections to create new, long-lasting and professionally fruitful relationships that Copland continued to nurture and support and which, in turn supported him as he entered the peak years of his career.

Sources & Further Reading

- Ansari, Emily Abrams. "Aaron Copland and the Politics of Cultural Diplomacy," Journal of the Society for American Music (vol. 5, no. 3): 335-364.

- Berger, Arthur. Aaron Copland. New York: Oxford University Press, 1953.

- Berger, Arthur. Reflections of an American Composer. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

- Copland, Aaron and Vivian Perlis. The Complete Copland. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2013.

- Hess, Carol A. Aaron Copland in Latin America. Chicago: University of Illinois, 2023.

- Kitson, Richard. "Complete Introduction to Modern Music Magazine." In Retrospective Index to Music Periodicals (1760–1966). https://ripm.org/?page=JournalInfo&ABB=MMU Accessed 27 April 2025.

- Lederman, Minna. The Life and Death of a Small Magazine (Modern Music, 1924–1946). Brooklyn, NY, Institute for Studies in American Music,1983.

- "League of Composers/International Society for Contemporary Music." http://leagueofcomposers.org Accessed 30 April 2025.

- Library of Congress. "Primary Sources for Latin American Composers at the Library of Congress." https://guides.loc.gov/latin-american-composers-primary-sources Accessed 16 May 2025

- Library of Congress. "Biography: Serge Koussevitzky" and "Collection: Serge Koussevitzky Archive." https://www.loc.gov/item/n81142296/serge-koussevitzky/ and https://www.loc.gov/collections/serge-koussevitzky-archive/about-this-collection/ Accessed 1 May 2025.

- McLucas, Anne Dhu. "Seeger, Charles (Louis Jr.)" Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2258144 Published online 31 January 2014. Accessed 17 February 2025.

- Oja, Carol. Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Page, Tim. "At 67, Bernstein Comes Home to Carnegie Hall." New York Times, September 20, 1985, Section C, Page 3. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/09/20/arts/at-67-bernstein-comes-home-to-carnegie-hall.html

- Pollack, Howard. "Piston, Walter (Hamor)." Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.21851 Published online in 2001. Accessed 9 April 2025.

- Rosenfeld, Paul. “The Newest American Composers,” Modern Music, XV: 3 (March-April 1938), 153.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas. Music of Latin America. New York: Thomas Y Crowell, 1945.

- Swayne, Steve. "William Schuman, WW2, and the Pulitzer Prize." The Musical Quarterly, v.89, No 2/3 (Summer-Fall 2006) 273-320.

- Thomson, Virgil. American Music Since 1910. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971.

- Tommasini, Anthony. Virgil Thomson: Composer on the Aisle. New York, W.W. Norton,1997.

- Von Glahn, Denise. Circle of Winners: How the Guggenheim Foundation Composition Awards Shaped American Music Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023.