Aaron Copland was never just a composer; he was always an American composer. From the moment he sailed for Paris at age 20, his nationality was his main identifying trait. Certainly, Copland's identity, tastes, influences, and musical style cannot be contained by the adjective "American," but Copland often wrote and thought about himself in those terms. Today, we’ll begin a two-part reflection on some of Copland's best-known statements about being American.

The comments Copland made on being a composer in the United States fall into three rough categories. Some are autobiographical. Others describe techniques composers could use to make music sound American. Still others concern society: what was the composer's role in the U.S, and who were the audiences for concert music?

An American Autobiography

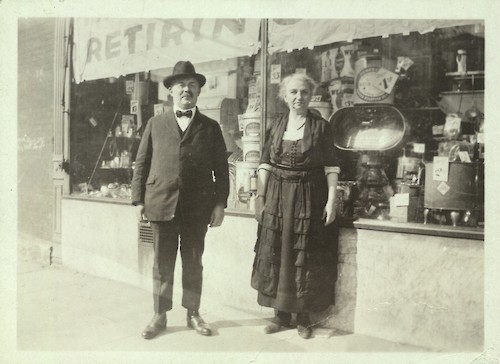

Copland's first significant published autobiographical statement appeared in The Magazine of Art in 1939. In his telling, his origins were thoroughly American, but far from idyllic.

I was born on a street in Brooklyn that can only be described as drab. It had none of the garish color of the ghetto, none of the charm of an old New England thoroughfare, or even the rawness of a pioneer street. It was simply drab. It probably resembled most one of the outer districts of lower middle-class London, except that it was peopled largely by Italians, Irish, and Negroes. I mention it because it was there that I spent the first twenty years of my life. Also, because it fills me with mild wonder each time I realize that a musician was born on that street.(ONM, 212)

With no professional musicians in his family, the idea of becoming a composer only "gradually dawned" on him at about age fifteen. He soon realized that European training was a necessary calling card for any classical musician in the Americas. His Parisian composition teacher, the renowned pedagogue Nadia Boulanger, strongly encouraged him to sound American during his student years in Europe. Upon his return to New York, he enthusiastically joined an ongoing effort to establish a national artistic and literary culture that would command international respect.

The Boston-based Russian-born conductor Serge Koussevitzky and some other generous American patrons helped Copland launch his career. During the Great Depression, he resourcefully sought opportunities outside the concert hall, altering his musical language as needed to suit the purpose at hand.

[After the stimulating decade of the 1920s] I began to feel an increasing dissatisfaction with the relations of the music-loving public and the living composer . . . It seemed to me that we composers were in danger of working in a vacuum. Moreover, an entirely new public for music had grown up around the radio and phonograph. It made no sense to ignore them and to continue writing as if they did not exist. I felt that it was worth the effort to see if I couldn't say what I had to say in the simplest possible terms.(ONM, 228-229)

He recycled this basic narrative throughout his life. The article became a chapter in his 1941 book Our New Music. From there, the "simplest possible terms" paragraph was quoted in dozens of mass-market books like The Book of Modern Composers and Musical Trends in the 20th Century well into the 1960s. Although he wrote complicated works alongside the simple ones, he struggled to escape the "simplicity" label in subsequent years.

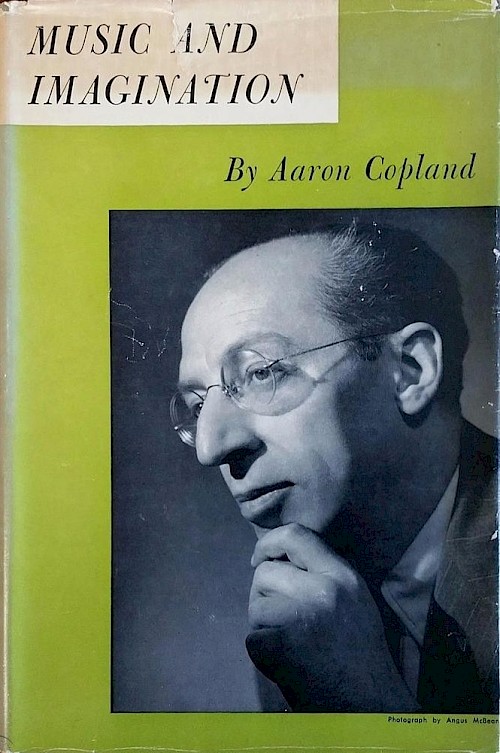

In 1951, Copland qualified his search for "simplicity" in the autobiographical portion of his Norton lectures at Harvard: "This desire of mine to find a musical vernacular, which, as language, would cause no difficulties to my listeners, was perhaps nothing more than a recrudescence of my old interest in making a connection between music and the life about me,"(M&I, 108-109) connecting "drab" Brooklyn with the elegant concert hall tradition.

When the revised version of Our New Music appeared in 1968, he protested the "simplicity" narrative in no uncertain terms. "The writing of an autobiographical sketch in mid-career is fraught with peril. Commentators, pleased to be able to quote literally, are convinced they have pinned the composer down for all time." The "simplest possible terms" paragraphs in Our New Music, he called "long out of date" and said had "done me considerable harm. [They] were taken to mean that I had . . . turned my back on the cultivated audience . . . and henceforth would write music solely for the 'masses.'"(TNM, 161) In eight new pages (the original sketch was only ten), he reviews the 1920s and 1930s, then carries the narrative forward through the establishment of Tanglewood, his international travels for the U.S. Government, his conducting activities, and his exploration of complex new compositional techniques of European origin.

Copland emphasized different elements of his history in different contexts and at different times. Over a career spanning more than five decades, his style, his priorities, his techniques shifted and expanded. But his identification as an American composer remained constant.

Sounding American

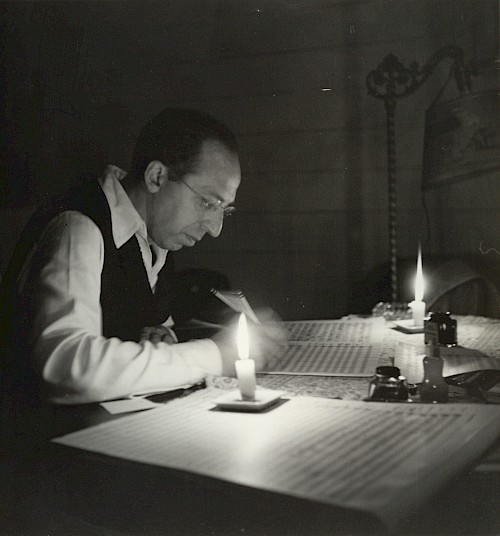

Copland spent at least twenty years seeking to make his music sound American. In the mid 1920s, he borrowed gestures, chord progressions, rhythms, and bits of melody from what he called "jazz": the syncopated dance music that permeated popular culture. "I was preoccupied with the idea of adding to the great history of serious music something with an American accent . . . [Jazz] was an easy way to be American—quickly American—in a way that the world could recognize as American," he told Vivian Perlis in the 1970s.(Perlis, 309)

Music for the Theatre, the Piano Concerto, and several of the Four Piano Blues date from this short-lived "jazzy" period. And long after the "jazzy" phase passed, he described a certain lively rhythmic freedom with African roots, which was an inherently American characteristic audible in both serious and popular music. "The most potent influence [of jazz] on the technical side was that of rhythm," he wrote in Our New Music.(ONM, 89)

Beginning in the 1930s, Copland mined American folk music for motives, harmonies, textures, and even complete melodies that would make his music sound overtly American. He found fiddle tunes and folk songs in collections made by folklorists like John Lomax and Carl Sandburg. El Salón México, Billy The Kid, Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo, Appalachian Spring, Old American Songs, and Lincoln Portrait were among the well-known results.

Many American composers in the 1930s and 1940s sought an American sound. Copland put that ideal into words when describing Roy Harris's best music.

I feel its American quality strongly . . . music of real sweep and breadth, with power and emotional depth such as only a generously built country could produce. It is American in rhythm . . . with a jerky, nervous quality that is peculiarly our own. It is crude and unabashed at times, with occasional blobs and yawps of sound that [Walt] Whitman would have approved of.(ONM, 165)

He recalled decades later, "I was preoccupied with the idea of adding to the great history of serious music something with an American accent."(Perlis, 309) As time passed, sounding American became less important for Copland and his peers.(TNM, 97n) In 1959, he suggested reasons for the shift:

The older generation fought hard to free American composition from the dominance of European models because that struggle was basic to the establishment of an American music. The young composer of today, on the other hand, seems to be fighting hard to stay abreast of a fast-moving post-World War II European musical scene."(CoM, 176)

After about 1950, Copland's writings evaluated American compositions in international terms and focused less on any American accent. One no longer needed to sound American to be American.

Representing America?

Of course, Copland's efforts to "sound American" were not as straightforward as his 1970s comments imply. American identity itself is multifaceted and fraught. Scholars agree that the Americanist cultural movement of the 1930s and 1940s gave rise to much affirmative, enduring art. At the same time, the folk song collectors whom Copland relied on were selective about which music they preserved; Copland's own choices added another layer of reinterpretation. One might protest that neither the folk being celebrated, nor the folk doing the celebrating were a representative cross-section of the American experience. Some scholars suggest the movement even did harm by misrepresenting history and marginalizing important perspectives (for example, David VanderHamm in “Simple Shaker Folk: Appropriation, American Identity, and Appalachian Spring”).

However widely Copland's music came to symbolize America, his own stated motives were more modest. He wanted a place in American society. Behind his efforts to establish an American autobiography, behind his quest to write American-sounding music, was the desire to fit in. “The two things that seemed always to have been so separate in America—music and the life about me—must be made to touch,” he wrote in 1952, describing the continuous "conviction" that emerged upon his return from Europe in the 1920s.(M&I, 97-98)

What was the composer's role in the U.S.? How—and why—should it change? Who were the audiences for chamber and symphonic music in America? Next month, we’ll pick up with another category of Copland's thoughts on being American: his place, as a composer, in American society.

Sources & Further Reading:

- CoM. Aaron Copland, Copland on Music. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1960.

- M&I. Aaron Copland, Music and Imagination. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1952.

- ONM. Aaron Copland, Our New Music: Leading Composers in Europe and America. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1941. The autobiographical "Composer from Brooklyn" chapter (pp. 212-230) was first published in Magazine of Art 32 (September 1939), pp. 522-523.

- Perlis. Aaron Copland and Vivian Perlis, interviews (1975-1978). In Vivian Perlis and Libby Van Cleve, Composers' Voices from Ives to Ellington: An Oral History of American Music (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), pp. 300-329.

- TNM. Aaron Copland, The New Music. New York: W.W. Norton, 1968.

- VanderHamm, David. “Simple Shaker Folk: Appropriation, American Identity, and Appalachian Spring,” American Music 36, no. 4 (2018), pp. 507–26.