I appreciate the opportunity to be a guest contributor to The Aaron Copland Fund’s “Midday Thoughts” series as Copland has been on my mind quite a lot this year. One hundred years ago, in 1925, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation announced its first fellows in fifteen award categories. Beyond music composition, awardees were named in general nonfiction, classics, history-British, history-Renaissance, literature-English, literature-medieval, religion, botany, chemistry, mathematics, medicine, neuroscience, political science, and psychology; in subsequent decades other categories would be added. And one hundred years ago, Aaron Copland was the first music composition fellow. His fellowship was renewed in 1926 and over the ensuing years, Copland’s career and the Foundation’s growing reputation would be inextricably intertwined.

Defining Copland’s Voice

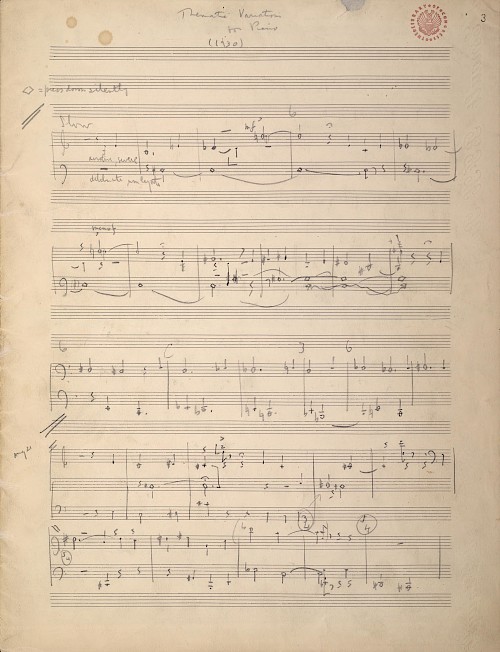

But it’s not just this double anniversary year that brings Copland to my mind. While better known as a Charles Ives scholar, perhaps, I’ve been taken by this musical polyglot for decades. It turns out that the many recent sesquicentennial celebrations of Ives have made me reflect once again on the different but equally powerful impacts Copland and Ives have exerted on U.S. American music culture. In graduate school while writing a dissertation titled “Reconciliations: Time, Space, and the American Place in the Music of Charles Ives,” I also wrote a paper that compared three early piano works by Aaron Copland: his first published piece, The Cat and the Mouse written in 1921, shortly before he began his studies with Nadia Boulanger; Passacaglia, composed between 1921 and 1922, which he dedicated to Mlle. Boulanger; and Piano Variations, written over a ten-month period in 1930. He premiered that work-in-progress at the 1930 New Music Festival (a Copland-lead initiative) at Yaddo, the artists’ retreat in Saratoga Springs, New York, and gave its official complete premiere in January 1931 at a League of Composers Concert. Three pieces written within a decade, the last composed when Copland was twenty-nine years old, would, I hoped, provide a window into Copland’s musical vocabulary. And they did, to an extent.

Although the fluency, flexibility, and facility that would come to be associated with the composer could be cited as evidence of a chameleon-like nature by detractors, Copland’s musical polylingualism reflected his awareness of multiple sounds and sources. It served him well not only as a composer familiar with a range of styles and genres, which allowed him to fulfill commissions for a variety of ensembles and media, but also as a living exemplar of the rich variety of American artistic expression. In this regard, he shared much with Ives, who understood Bach’s counterpoint and Tin Pan Alley tunes equally well and referenced them both in his music. Copland’s natural musical polylingualism, however, proved to be essential to him when, starting in 1927, he was asked to read through dozens of Guggenheim music composition fellowship applications and their accompanying scores from a variety of hopeful young composers. Copland revealed himself to possess an open mind to a wide range of musical thought and creation.

Musical Values

As we enter the second quarter of the twenty-first century, it is hard to imagine Copland as anything but the beloved, globe-trotting composer, conductor, writer, senior cultural diplomat, and American music icon he came to be by the time of his death in 1990. But in January 1925, Aaron Copland, born in Brooklyn on November 14, 1900, had just turned twenty-four years old. He was an aspiring young composer, little known beyond his teachers Rubin Goldmark in New York, Nadia Boulanger at Fontainebleau, and a handful of extremely well-placed advocates. When Boulanger premiered Copland’s Symphony for Organ and Orchestra in early 1925—first in New York with Walter Damrosch conducting, and then in Boston, with the newly appointed conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Serge Koussevitsky—their combined efforts provided an incomparable debut for Copland who had just returned from a three-year study sojourn in France. It had been Koussevitsky who asked Copland to write the Organ Symphony for his friend Boulanger, thus establishing that alliance. The Copland-Koussevitsky friendship lasted until the conductor died in 1951, and Copland remained a faithful proponent of Mademoiselle until her death in 1979. Her pedagogical values, ones that privileged discipline, technical mastery, and a personal voice above all, guided Copland as a composer, teacher, and evaluator of Guggenheim music composition applicants.

In Circle of Winners: How the Guggenheim Foundation Composition Awards Shaped American Music Culture, I noted that based on 110 evaluations that Copland wrote on successful candidates between the late 1920s and the mid-1980s, “his basic standards remained remarkably consistent over the years, even as he composed in different styles himself. Most important to him was a clear, identifiable voice, a distinct musical personality.” It is telling that in Boulanger’s letter of recommendation written on Copland’s behalf in 1925, she commented on her student’s “quite exceptional musical personality.” In his own letters on others decades later, “Copland expressed a desire to hear the ‘personal’ composer, ‘real’ emotion and true feeling.” He had little time for “flair, or mere cleverness (signs of immaturity,)” or composers whose voice “was suppressed by overwhelming allegiance to academic trends—the mind over the musical impulse. He wanted proof of a composer’s ability to handle the large forms but had no tolerance for gratuitous intellectualism.” I concluded that despite Copland seldom exposing personal vulnerability in his own music “he sought, above all, evidence of ‘vital,’ ‘alive’ music that originated in feeling” in the work of applicants.

Shared Benefit

Copland’s emergence on the US scene in early 1925 couldn’t have been better timed for solidifying his relationship with the Foundation. The nation was fresh from a winning alliance with World War I victors, and it occupied a newly solidified presence on the world stage. After decades of composers seeking a national voice while imitating European musical languages, Copland was positioned to deliver the United States one version of its own music culture, a goal that he had expressed to Harold Clurman when the two men sailed home from their studies in France. Clurman sought to do the same for American theatre. When, a couple of months after Copland’s return to New York, the newly created John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation announced its intention to award year-long fellowships across a number of disciplines, Copland was optimally placed in the public eye to be a strong contender for an award in music composition.

The Foundation had spent the previous year consulting with educational leaders clarifying their goals, studying best philanthropic practices, and adapting Rhodes Scholarship values and processes to its own ends. It refined its administrative structure and designed its policies before announcing the fellowships. With none of the Foundation’s principal administrators knowledgeable about music, and few of the educational leaders who were consulted in 1924 optimistic about the ability of anyone to judge the value of music or a musical “genius,” the Foundation was late to identify any music consultants or name a music adviser. Thomas Whitney Surette (1861-1941), the hastily appointed, questionably qualified man who was appointed in January 1925, was not subject to the Foundation’s systematic and rigorous vetting process that they had used to identify accomplished advisory board members in other categories. Without any regular institutional affiliation beyond that of his private amateur-focused Concord Summer School, Surette was on his own. Despite his limited musical credentials for the job, however, thanks to his wife’s family connections he enjoyed associations with well-placed elites in the Northeast and on the continent in England, France, and Germany, as well as an informal relationship with Nadia Boulanger. The sixty-four-year-old also had the time, and was close by in New York, and available.

Given Copland’s well-advertised Organ Symphony premiere, Surette didn’t have to work to identify or promote a suitable awardee in the first year. Having convinced the Foundation of his impeccable taste and the wisdom of his “personal method” of selecting winners, which required an in-person interview with him at the Guggenheim Foundation offices, Surette was never required to justify his choices. In the case of Aaron Copland, however, he didn’t need to; concert reviewers did the work for him. With Copland’s newly minted French credentials and successful debuts in two American cultural centers that were covered in major newspapers, it was easy and wise for Surette to support and promote Copland.

Between 1925 and 1940, the Foundation cultivated sympathetic contacts and pipelines with other organizations, selected early fellows, and continuously expanded its sphere of influence, responding to challenges from within and without and claiming its place as a new type of American institution—a strategically positioned, increasingly powerful, large private philanthropic network with international interests, resources, and ambitions. Within the same period, using his significant abilities as a writer as well as a composer, Copland established his position as a widely-regarded spokesperson for American music culture. As the Foundation drew upon its elite network of university administrators, faculty at select institutions, and well-placed supporters for advice, applicants, and advertising, it owed its early credibility in the category of music composition to Aaron Copland as much as he owed them gratitude for selecting him to be their original standard bearer.

Conclusion

For over sixty years Copland remained true to his goal of shaping a high-art American music culture. Late in life he recalled his pact with Clurman: “We both knew when we returned from Europe in 1924 that we wanted to be spokesmen of our generation in American arts.” (Copland: 1900 Through 1942, 60). Copland’s ability to write persuasive prose, and his willingness to champion the cause of other young composers (as well as his multiple musical fluencies, impeccable craft, indefatigable energy, easy manner, interpersonal savvy, organizational prowess, and ambition for his nation’s culture), meant that his selection as the first John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation music composition fellow in 1925 launched not only his career, but also firmly established the reasonableness of a fellowship for creative work in music specifically, and the credibility of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation more broadly. Copland used the platform that the Foundation provided and built another that served himself, one that accommodated a large circle of composer colleagues and excited the nation’s nascent concert-music culture. He became the spokesperson he had envisioned.

Denise Von Glahn, Professor of Musicology in the College of Music at Florida State University, is the author of essays, chapters, and articles, as well as five books on various aspects of American music culture. She currently serves as President of the Society for American Music.

Sources & Further Reading

- Copland, Aaron. "America's Young Men of Promise." Modern Music, 3, no. 3, 1926.

- Copland, Aaron. "Our Younger Generation Ten Years Later." Modern Music, 8, no. 4, 1936.

- Copland, Aaron, and Vivian Perlis. Copland: 1900 through 1942. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1984.

- Copland, Aaron, and Vivian Perlis. Copland: Since 1943. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999.

- Davis, John H. The Guggenheims: An American Epic. New York: William Morrow, 1978.

- Leonard, Kendra Preston. Conservatoire Americain: A History. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 2007.

- Oja, Carol J. Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Page, Tim. "The Trailblazer: Aaron Copland and the Festivals of American Music." In Yaddo: Making American Culture, edited by Micki McGee, 31-40. New York: Columbia University Press, New York Public Library, 2008.

- Pollack, Howard. Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man. New York: Henry Holt, 1999.

- Von Glahn, Denise. Circle of Winners: How the Guggenheim Foundation Composition Awards Shaped American Music Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023.