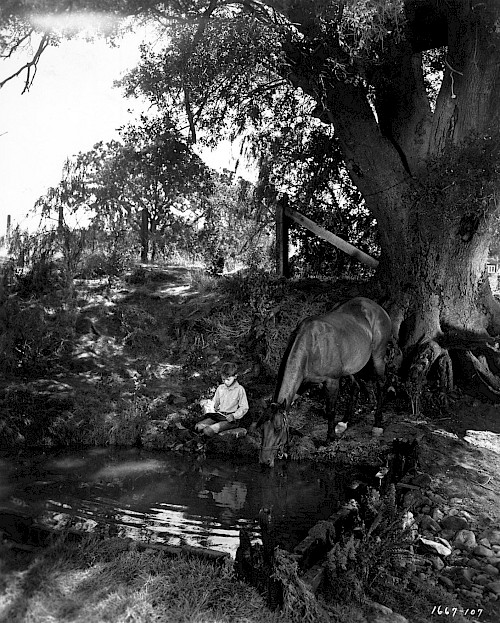

Aaron Copland's celebrated film score to The Red Pony was first heard in movie theaters 75 years ago, marking a significant moment in cinematic history. The film had been completed two years earlier, in 1947. While waiting for the movie to be released, Copland created The Red Pony Suite to fulfill a commission from conductor Efram Kurtz, who premiered it in October 1948 with the Houston Symphony. The suite's six movements were taken directly from episodes written for the film, though the order was not preserved. First is “Morning on the Ranch,” followed by “The Gift,” “Dream March and Circus Music,” “Walk to the Bunkhouse,” “Grandfather's Story,” and “Happy Ending.” In 1966, Copland arranged a twelve-minute suite for band, using movements III-VI.

The film's scriptwriter was John Steinbeck, who drew the material from his 1937 novella of the same name. Lewis Milestone produced and directed the film.

Childhood

Life, death and the painful realities of maturing are pervasive themes throughout The Red Pony, spanning the book, the script, and even the music. Billboard complimented the novel by stating that "The Red Pony, [by] John Steinbeck, [is a] wrenching story of adolescent initiation into the world of death, birth, and disappointment." Yet Copland, Steinbeck, and Milestone, it seems, disagreed on how appropriate the material was for children. Steinbeck's novella centers on a young protagonist named Jody, who becomes "Tom" in the film adaptation.

Critics lamented that a blanket of post-war optimism was thrown over the sharp edges of Steinbeck's novel, a coming-of-age tale about a boy living on an isolated California farm. Many critics lamented that the film shortened or softened harsher elements of the story, as when Jody beats a vulture to death upon discovering the carcass of his beloved pony. In the final scene of the movie, Jody/Tom's new pony is born safely, without the death of the mare, unlike Steinbeck's original version.

Despite his direct involvement with the movie, Steinbeck expressed discomfort with the final cinematic interpretation, lamenting to Copland, “Except for the music, I am not unpleased that this film, to the best of my knowledge, is still held as hostage in a bank vault.” Steinbeck knew and liked Copland's suite version, but he refused to write a new script "for children" to go along with it. He believed his original novel spoke best to children; he said in his response to Copland's query (July 17, 1964):

"Children have always understood the little book 'The Red Pony.' They have been saddened by it, as I was when it happened to me, but they have not been destroyed by it," Steinbeck wrote. He commended Copland for infusing the suite with a delicate balance of somberness and gaiety, underscoring the profound significance of life's dualities. Steinbeck recalled specific musical passages in Copland's score, such as the depiction of an owl's predatory swoop and the intense confrontation between Jody and a buzzard, as poignant musical depictions of humanity's defiance against mortality.

In Steinbeck's view, children possess a unique perspective on mortality, contemplating its weighty implications with a depth often overlooked by adults. To them, the specter of death looms large, shaping their understanding of the world and their place within it.

Folk Music in The Red Pony

Accordingly, Copland wrote The Red Pony music to depict the views of a child. Copland had by 1947 written many works for adults that quoted folk tunes (Billy The Kid, Lincoln Portrait, Appalachian Spring), but it is also true that folk tunes were gaining a solid foothold in American public education by then. The triadic simplicity of much of Copland's musical language for The Red Pony is described as folklike. In crafting the musical score to encapsulate a child's perspective, Copland not only continued his tradition of incorporating folk tunes, prevalent in his earlier compositions for adult audience, but also mirrored the growing presence of folk melodies in American public education during the era.

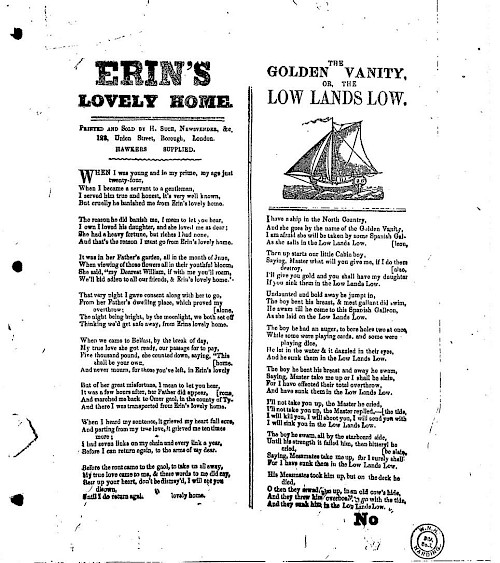

However, Copland's assertion that The Red Pony melodies are entirely his own "except for a tinge of 'so long old paint'" (Complete Copland, 194) is not entirely accurate. What the standard biographical sources fail to note is that "The Golden Willow Tree," a folksong later featured in his Old American Songs, Set II (1952), appears as a recurring theme in the first and last movements of the suite. By 1947, when Copland composed the film score, several recordings of the tune had been released, including renditions by the Carter Family (“Sinking in the Lonesome Sea,” 1935), Justus Begley (recorded by Alan Lomax in 1937), and Pete Seeger with the Almanac Singers (“The Golden Vanity,” 1941).

Begley's rendition of "The Golden Willow Tree" was clearly Copland's direct inspiration, for Copland retains several features unique to the Lomax recording. More than the other versions, Begley's has a tonal ambiguity created by his emphasis on scale degrees 2 and 4, coupled with the absence of a strong leading tone (the half step below scale degree 1). These elements that seem to have appealed to Copland's compositional sensibilities, as they are retained in the first and last movements of The Red Pony Suite, and in his Old American Songs setting.

Copland readily acknowledged that he chose folk melodies primarily for their musical potential. Yet one wonders whether the lyrics to "The Golden Willow Tree/Golden Vanity" resonated for Copland as he began scoring the film, given Steinbeck's life-and-death subject matter. Known since the 19th century as "Child Ballad #286," the poetic tale likely originated in England as early as 1635. It tells of a brave youth who saves his captain and crew by drilling holes in the bow of a rival ship, only to be betrayed by his own captain and left to drown. The notorious harshness of the Child Ballads and their adaptations, as preserved in the hills of Appalachia, no doubt contributed to the renaissance of interest in rural folk culture among Depression-era writers like Steinbeck and other artists of the early- to mid-twentieth century U.S.

Youth and Copland's score

Whether Steinbeck approved or not, it’s worth acknowledging Copland's intuition that the music held special resonance for young people. Initially titled "Children's Suite from the Red Pony," an early recording by Thomas Schippers in 1952 and an early Copland manuscript bearing the subtitle "Suite for Children" hinted at this conviction, although the latter was later crossed out. Despite the subtitle's abandonment, the music's frequent association with young listeners and young performers likely contributed significantly to the work's widespread recognition.

Educational institutions have played a significant role in disseminating Aaron Copland's music, particularly The Red Pony Suite, throughout American society. Its widespread adoption at the collegiate and high school levels, along with its integration into published and recorded educational materials, has served as many listeners' first exposure to Copland's work.

Many prestigious institutions have featured performances of The Red Pony Suite arranged for wind ensemble. Examples include Indiana University (1972), the New England Conservatory (1986, 1983), Ohio Wesleyan University (circa 1980), Texas Tech University (1991), and the Eastman School of Music (versions in 1996 & 1997). Orchestral performances by student musicians date back at least to 1964, when Copland worked with the Portland Youth Symphony for their 40th anniversary.

Since the 1960s, The Red Pony Suite has found its way into educational materials, further enhancing its accessibility to students. It has been featured in textbook soundtracks like "Adventures in Music Grade 3" (RCA, 1960s), "Exploring Music" (1967), "Materials of Music" by Macmillan (1975), "Spectrum of Music" by Schirmer Records (circa 1980), "The Music Connection" by Silver Burdett & Ginn (“Circus Music” only, 1995), a "Classical Zoo" recording (1995), and materials issued by McGraw Hill Education in the 2010s ("Spotlight on Music" and "Music! Its Role and Importance in Our Lives").

Music from The Red Pony Suite has been featured in arrangements for numerous high school marching bands in recent years. Recorded performances from marching band and drum corps competitions from the 1980s and 1990s continue to circulate, attesting to its lasting influence. These educational uses of The Red Pony Suite have not only introduced Copland's music to successive generations but also foster its widespread appreciation and integration into many facets of American cultural life.

Copland’s Score in American Culture

The music from The Red Pony endures because it exceeds its original contexts. Unlimited by a specific film director's postwar conception, a famous author's earlier vision, music educators, or any single audience, the music from Copland's film score has permeated American culture through multiple avenues. Three of the major U.S. military bands have the band suite in their repertoire: the US Army Field Band, the US Navy Band (recorded in 2014), and the US Marine Band (recorded and released in 2000 & 2008). Dance companies such as the Columbus Dance Theatre and the Dayton Ballet have incorporated The Red Pony Suite into their performances.

Fiction films have featured music from The Red Pony, including A House on A Hill, about an aging architect. More prominently, Spike Lee used it along with many other Copland works in the soundtrack to He Got Game, the 1998 film about a teenage basketball star from a poor urban neighborhood—a usage which prompted scholars to reflect on matters of race and reappropriation (Gabbard, Doughty), even as it broadened the associations of Copland's music well beyond ranches and cowboys.

An assortment of documentaries have used The Red Pony Suite to underscore their imagery. The subjects of these documentaries range from Letchworth State Park, Jamestown (for Channel 4 in Britain), the National Park Service, and the Works Progress Administration, to the Paralympics. In addition, the "Circus Music" movement has been widely distributed by Bose and other companies to demonstrate the capabilities of their audio equipment. In the early 1980s, a televised concert series called "In Performance at the White House," used a theme from The Red Pony as its signature music. And the video game Civilization V by 2K Games further extended the work's reach to new audiences by incorporating music from the suite.

Personal and Cultural Influences on the Score

The Red Pony film score is rarely heard today in its original cinematic context. Paradoxically, certain criticisms frequently levied against Milestone's film may articulate the very conditions that allowed Copland's creativity to flourish. Additionally, both Copland and Milestone may have been influenced by emerging postwar aesthetic trends that audiences were not yet prepared to fully appreciate. In Copland's instance, a new personal relationship played a pivotal role in his decision to undertake the project, driven by considerations both aesthetic and practical.

One of the primary criticisms of Milestone’s The Red Pony was its perceived tendency to ramble or meander. In a contemporary review for The New York Times, film critic Bosley Crowther remarked that "[T]he story does ramble, and its several interlaced strands are often permitted to dangle or get lost in the leisurely account." Crowther also noted director Lewis Milestone's adoption of a casual directing style, which, in his view, contributed to the film's languid quality.

Interestingly, similar criticisms would soon be directed toward Aaron Copland's 1952 opera The Tender Land, another composition completed during the early post-war years. This connection is further emphasized by the involvement of Erik Johns, who not only had a romantic relationship with Copland during the composition of both scores but also wrote the libretto for The Tender Land. Scholar Chris Patton has highlighted the influence of Vedantic thought in Copland's The Tender Land score, creating an emphasis on character development and gentle shifts in perspective, and recirculating themes of life, loss, and meaningful change that comes through self-realization.

Howard Pollack, in his Copland biography, notes Johns's involvement in Eastern philosophies and his significance to Copland's creative endeavors, including in The Red Pony film project. Correspondence between Copland and Johns reveals the personal dynamics at play, with Johns hoping for Copland's presence in California to resume their affair during the ten weeks required for the film scoring project.

While some viewed the film's meandering narrative as a flaw, Copland saw it as a virtue: the less action-packed structure of the film allowed Copland to write well-developed music. Pollack suggests that Copland appreciated the leisurely pace and interwoven narrative strands because they provided him with more opportunities to be more "musical" in his score, allowing for a deeper exploration of themes and emotions; it also made the score a better source for his suite than the conventional film, which called for frequently changing, short bursts of action-dependent music.

Copland emphasized that his decision to accept The Red Pony scoring job was motivated by the film's departure from the typical Western narrative, stating, "It is not a typical Western with gunmen and Indians. There is a minimum of action of a dramatic or startling kind. The story gets its warmth and sensitive quality from the character studies." He further articulated his aim to compose music that would seamlessly blend with the film's quiet yet moving narrative, eschewing overt dramatic gestures for a more subtle, reflective approach.

In considering the "meandering" character-sketch aesthetic of the Milestone film adaptation of The Red Pony, it is intriguing to ponder the role Erik Johns may have played in introducing Aaron Copland to Eastern Vedantic aesthetic philosophy. Johns's involvement in both Copland's personal life and creative endeavors, particularly during the composition of The Tender Land opera and The Red Pony film score, suggests a significant influence. Scholars have highlighted Copland's and Johns's shared interest in Eastern philosophies, which likely permeated Copland's compositional approach and artistic sensibilities.

Through Johns's influence, Copland may have been exposed to the contemplative, introspective qualities inherent in Vedantic thought, which align closely with the "meandering" narrative style and character-focused aesthetic of the Milestone film. This connection underscores the intricate interplay between personal relationships, philosophical influences, and artistic expression within the creative process. As such, Erik Johns's role in introducing Copland to Eastern Vedantic aesthetic philosophy provides a compelling lens through which to understand the nuanced layers of meaning and inspiration that enrich the cinematic adaptation of The Red Pony.

Traditional Dissemination: Performances and Recordings

If film was neglected for reaching for a new aesthetic ideal, Copland’s score, especially the Suite, suffered no such fate. Since its premiere, The Red Pony Suite has a robust history of dissemination as concert music via live performances and commercial recordings. Copland himself conducted performances during his 1960 USSR diplomatic tour and at the Aspen Music Festival the same year; in 1975, he conducted a performance in London for Columbia Records that was later reissued on CD by Sony. Throughout the decades, excerpts from the suite have appeared on audio compilations for adults, under titles like "Greatest Hits," "Cinema Classics," and "Music to Have Fun By."

Over the years, prominent conductors have led performances and issued recordings: Leopold Stokowski, André Previn, Howard Mitchell, Leonard Slatkin, and John Williams. Since 1999, the suite has been programmed dozens of times in cities from New York to Charlottesville Chicago to Tuscaloosa, Washington, D.C. to Portland, Oregon. The work is a special favorite at summer festivals, like Grant Park in Chicago, the Aspen Music Festival, and the Hollywood Bowl. Since 2012, there has been a surge of European performances, including in cities such as Siegen and Marbach in Germany, Bern in Switzerland, and at the Berlin Comic Opera.

In 2005, the American Film Institute inducted Copland's score into its hall of fame, as part of the "100 Years of Film Scores" list. The performance and recording history of The Red Pony Suite for orchestra, like that of Copland’s wind ensemble arrangement, reflects an enduring popularity and versatility across different musical contexts and geographical locations. These avenues of dissemination and recognition demonstrate the lasting cultural importance of Copland's music for The Red Pony in American society and beyond.

Sources & Further Reading

- Copland, Aaron and Vivian Perlis. The Complete Copland. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2013.

- Doughty, Ruth. "Scoring a Black Aesthetic: Music in the Films of Spike Lee." Ph.D. diss., Keele University, 2004.

- Gabbard, Krin. "Race and Reappropriation: Spike Lee Meets Aaron Copland." American Music, Vol. 18, No. 4 (Winter, 2000), 370-390. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3052582

- Patton, Christopher. "'The Tender Land': A New Look at Aaron Copland's Opera." American Music, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Autumn, 2002), 317-340. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1350129

- Pollack, Howard. Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man. New York: Henry Holt, 1999.